Visitors to Cornell’s storied Ithaca campus seldom think about the vast underground infrastructure that supplies electricity, potable water, chilled water, and heating to university buildings. Buried beneath their feet are miles and miles of underground piping, and other critical infrastructure that keep the lights on, computers humming, water running, staff and students warm—even when the temperature outside is frigid.

Much of the Ithaca campus is connected to what’s called a district energy system. This system delivers electricity, heating, and cooling from the central energy plant to buildings in the network, meaning that these buildings do not have individual heating or cooling sources.

Currently, the Central Energy Plant supplies steam through a network of underground piping, delivering heat to campus buildings. As this steam travels through the system, there’s roughly a 20% loss of efficiency. By replacing the steam with hot water, the inefficiency will be reduced—resulting in overall emissions reductions, cost savings, and safer operations—AND moving Cornell closer to its 2035 net zero emissions goal.

“The hot water conversion keeps our critical heating system operational and reliable, and it advances our decarbonization goals.” —Cole Tucker ’24, director of utilities distribution and energy management at Cornell

Renewing miles and miles of pipe

A team of about 24 staff members are charged with operations and maintenance of the utility distribution systems on campus. Their job is to make sure these systems operate seamlessly 24/7—so that even in the dead of winter, the lights in Willard Straight Hall shine brightly and the window seats in Olin Library stay warm and cozy.

Cornell’s campus is currently heated with steam generated by the university’s Central Energy Plant. This steam (about 450 degrees F) is distributed at high pressure through about 12 miles of pipe to the far-flung buildings on campus.

When it arrives at the door to a campus building, the steam is run through heat exchangers. These exchangers transfer the steam’s heat to the building’s closed loop hot water infrastructure, at temperatures suitable for use by building occupants (between 120-180 degrees F).

As the heat is transferred to the building, the steam condenses and the condensate is pumped back to the central energy plant, converted back into steam, and fed back into the system to provide heat.

While this may sound simple, it’s not. Chas Porter, thermal distribution manager for Cornell’s facilities and campus services department, explains.

“There's another roughly 10.5 miles of condensate pipe underground to get the cooled steam (that's been transferred from a gaseous state into a liquid) back to the Central Energy Plant, where we can heat it and make it into steam again,” he says.

The difference between steam and hot water is not just a matter of degree.

“When a droplet of water expands to become a steam gas bubble, it expands by 1,700 times,” he adds. “So, we have quite a bit larger steam pipes, versus our condensate pipes, to take up that difference in space.

Using every last ounce of heat

“With hot water, you can ring every last little ounce of heat out of the water and put it to use to heat the buildings.” —Chas Porter, thermal distribution manager, Cornell University

Cornell is currently working to swap out the steam heat on campus for a system run entirely on hot water. There are many wins associated with this conversion, including increased efficiency, better heat transfer, and safer operations.

Several compelling benefits are driving the steam to hot water (HW) conversion:

- HW INCREASES EFFICIENCY: As super-hot steam travels through the campus pipe system, there’s about a 20% loss of efficiency. By replacing the steam with hot water, this inefficiency will be reduced to about 5%. .

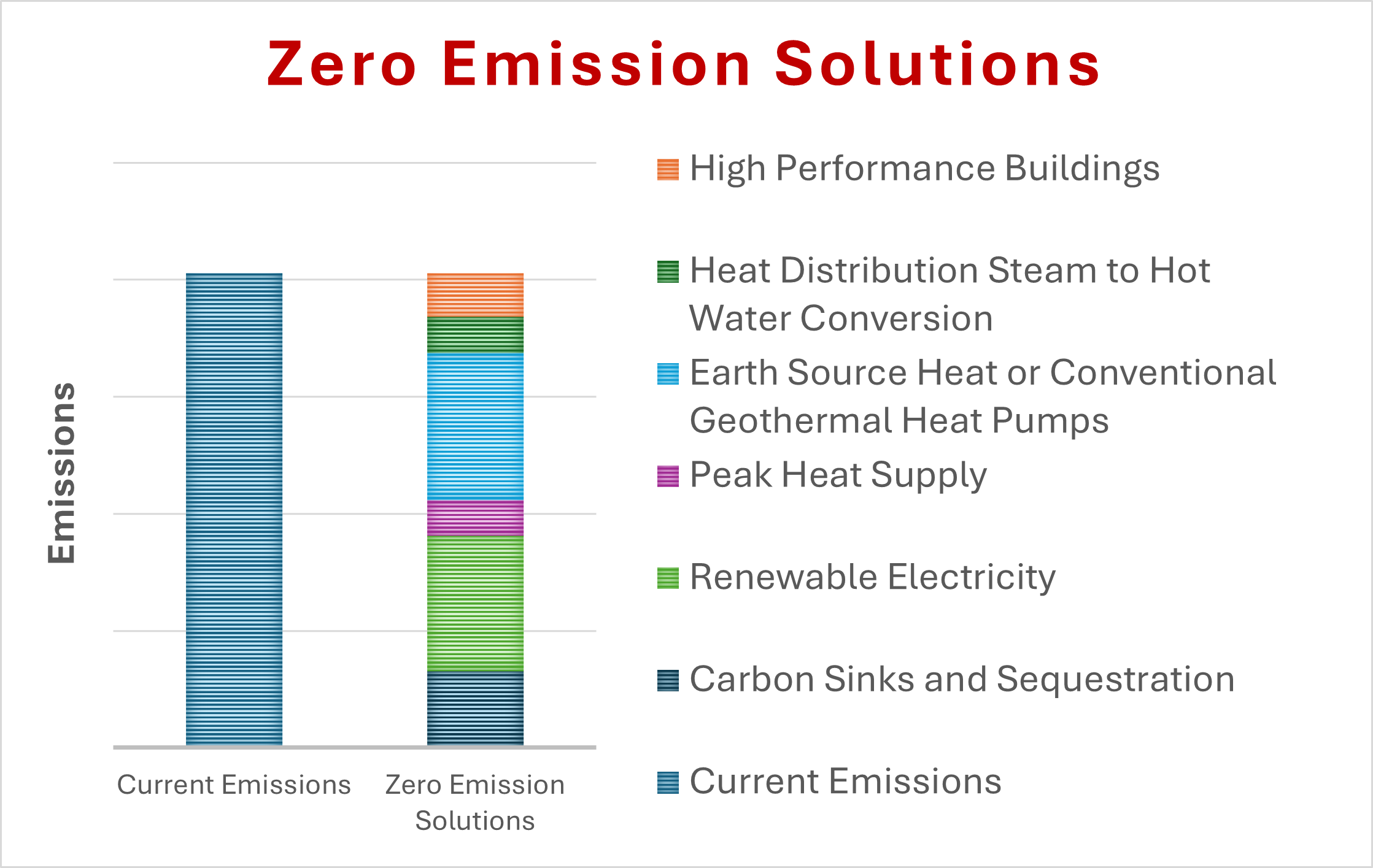

- HW REDUCES CAMPUS EMISSIONS: The conversion from steam to hot water is a key step in Cornell’s Climate Action Plan. Eliminating steam production results in a significant overall emissions reduction for campus because fossil-fuel free energy can be used to generate the lower temperature HW. This reduction is represented by the green bar on the Zero Emissions Solutions chart.

- HW SAVES MONEY (A LOT OF $): The overhead and maintenance cost for distributing steam heat to campus buildings is currently about $1M per year. The projected distribution cost for hot water heating is $270k per year. This represents a 73% reduction in costs associated with distributing heat to the campus.

- HW CREATES A CLOSED LOOP SYSTEM: The new hot water system Cornell is building is a closed loop—meaning that the same water circulates through the system again and again, with only minimal maintenance and chemical treatment.

- HW RENEWS CAMPUS INFRASTRUCTURE: Parts of the campus steam system are more than 100 years old. Replacing them with new hot water pipes that are better insulated will further reduce thermal losses and increase the overall efficiency of the system.

- HW IMPROVES SAFETY FOR WORKERS: There are inherent worker safety improvements by converting to hot water. Steam at high pressures and temperatures poses a risk for the staff working directly on the system—a risk that will be reduced with the switch to hot water.

- HW ENABLES FOSSIL-FREE HEAT SOURCES: A hot water distribution system enables fossil fuel-free sources of heat, including Earth Source Heat—a renewable heat source that Cornell is pursuing (the purple bar on the Zero Emissions Solution chart). Earth Source Heat generates hot water, not steam, and requires a hot water distribution system like the one Cornell is building.

Advancing Cornell’s decarbonization goals

“The hot water conversion keeps our critical heating system operational and reliable, and it advances our decarbonization goals,” says Cole Tucker ’24, director of utilities distribution and energy management at Cornell.

The campus-wide steam to hot water conversion is a critical component of Cornell’s plan to reach its 2035 carbon neutral goal. The conversion is currently 20% complete (i.e., about one-fifth of Cornell’s campus is now using hot water rather than steam heat).

The utilities thermal distribution team has been working diligently for more than 15 years to ensure that new buildings on campus (like the North Campus residential expansion), and renovations (like McGraw Hall) incorporate a steam to hot water conversion.

“We try to time the conversion to happen during campus upgrades,” Chas says. “That way, new construction and building renovations align with our hot water work and carbon neutrality goals.”

The team has already completed several hot water districts, including: the new residential buildings on North Campus, the North Campus High Rises/Low Rises, the newer West Campus dorm facilities, buildings along Sciences Drive, portions of East Campus, the new Atkinson Hall facility, Cornell Health, Friedman Wrestling Center, and the new CIS facility.

The construction has to be timed and planned very carefully, so as to keep services and people flowing on roadways, walkways, and into facilities. Recently, Cornell worked with a consultant to create a hot water master plan for the conversion to map out how best to accomplish a campus-wide switch by 2035.

“We need to dig up the majority of campus and upgrade the majority of buildings to make this work,” Cole notes. “Our master plan serves as a road map for how to do this. We know the system we need to build, and we’re ready to seize opportunities as they come up.”

In December 2024, the team completed the conversion to hot water heat in the Veterinary Medical Center (VMC) and East Campus Research Facility (ECRF). In its first few months of operation, Cole reports that, compared to the steam lines they replaced, the new VMC hot water lines are operating smoothly—with reduced risk and higher efficiency.

“Based on thermal performance alone,” he says, “they far exceed steam performance.”

Choreographing the parts of the dance

Jason Kelly, a distribution engineer with the team, provides site direction, engineering, and troubleshooting leadership for Cornell’s hot water conversion projects. Jason explains that the devil is in the details.

“A big challenge is keeping normal operations flowing, while roads, sidewalks, and buildings are being worked on,” Jason notes. “For example, Cornell’s VMC and ECRF are large buildings where day-to-day operations cannot be interrupted. The ongoing studies and research happening there rely on the utilities provided—and some of these studies may be years in the works.”

Think of all the sidewalks and pathways that traverse campus above ground. Chas says that provides a good sense of the underground network of infrastructure on campus, which is equally complex. Some of the pipes date back to the 1920s, while about 80 percent of the underground network has been upgraded and renewed.

“If unknown obstacles like old buried vaults or abandoned utilities are encountered (during the HW conversion),” Jason says, “the contractor will need to alter the pipe path and modify fittings. Every change in a pipe path needs to be reviewed by the company that supplies the pipe, so a stress analysis can be performed.”

Cole compares the hot water conversion project to a complex dance which is carefully choreographed. The goal is to coordinate the various tradespeople to minimize downtime and service interruptions to campus operations.

“The process can be disruptive, it’s messy, and it’s certainly not sexy, but it is active momentum towards carbon neutrality,” Cole says.

It’s also what he calls a “technology-agnostic” effort.

“We can confidently complete this conversion,” he explains, “while we figure out what our electric-based heat production systems will look like. Whether it is Earth Source Heat, ground-source, air-source, electric resistance, or storage doesn’t matter to the pipes we’re setting in the ground!”